What are some the advantages of the dotted lozenge style of rendering?

|

Detail of Hendrik Goltzius’ Vulcanus (1592), showing the dotted lozenge style of rendering tone

|

There are many drawing styles with long historical pedigrees of use (e.g. the return and hook strokes discussed in the earlier post, Passion in a Line), but one style that has virtually disappeared from use is the dotted lozenge (shown in the detail above). This distinctive style for rendering the effects of light and shade on a subject involves the artist in initially laying down a matrix of cross-hatched strokes (i.e. a set of parallel lines overlaid by another set of parallel lines aligned at an angle to the lines underneath as shown in the diagram below) and then inserting a dot in the centre of the diamond-shapes (lozenges) created in the cross-hatched matrix (see further below). The following discussion traces the evolution of this style and proposes some of the advantages for its use in the hope that the style may be revived with fresh applications for digital illustration.

|

Dotted lozenge style of rendering

|

The artist credited with the development of this rendering style is Hendrik Goltzius (1558–1617). Like all styles, it didn't simply appear one day. Instead, it evolved from the rendering practices of other artists and the Goltzius morphed them into the dotted lozenge manner of shading. For instance, Albrecht Durer (1471–1528) developed the line and dot technique for rending the transition from dark tones to light involving a set of parallel lines to represent shadows that taper off into dots aligned to the end of each line to represent the transition to light (see diagram below with detail of Durer’s famous engraving, Adam and Eve).

|

(left) Durer's line and dot style of rendering

(right) Detail of Durer’s Adam and Eve, 1504

|

Uploaded by ClarkArtInstitute on Nov 11, 2010

Even Durer’s style had it predecessors with engravers like the Master of the Playing Cards (active c.1425–50) who used parallel lines of varying length to represent tonal changes (see detail below of Saint Sebastian by the Master of the Playing Cards).

|

left) Master of the Playing Cards’ parallel lines of varying length style of rendering

(right) Detail of Master of the Playing Cards’ Saint Sebastian, c. 1425–50 |

Regarding the use of dots without any line work to render a tonal transition, Giulio Campagnola (c.1482–after1515) is credited with being the inventor of the “dotted manner” (i.e. stippling as shown below in the diagram and detail from Campagnola’s Venus Reclining in a Landscape) but the use of dots extends back earlier into the fifteenth century with the punched dots in metal-cut prints and far earlier to the first cave paintings.

|

(left) Campagnola’s dotted manner (stippling) of rendering

(right) Detail of Campagnola’s Venus Reclining in a Landscape, c.1508–09

|

The cross-hatching style had its own evolution as well. This style made its first appearance in the prints of Master ES (active c. 1450–67) (see diagram and detail below from The Visitation by Master ES). Here the type of cross-hatching features sets of straight aligned strokes that are multi-layered when dark tones are required and thinned in their layering for the light tones.

|

(left) Master ES’ cross-hatching style

(right) Detail of Master ES’ The Visitation, c.1450

|

This style of cross-hatching then evolved with Martin Schongauer (c.1448–1491) whose prints were the first to feature curved lines lightly delineating the contours of the subject in the cross-hatched strokes (see diagram and detail below of Schongauer’s Christ as the Man of Sorrows between The Virgin Mary and St John).

|

(left) Schongauer’s curved cross-hatching style

(right) Detail of Schongauer’s Christ as the Man of Sorrows between The Virgin Mary and St John, c.1471–73

|

Even the attributes of the lines used in shading had evolved by the time of Goltizius allowing him to build upon Schongauer’s curved cross-hatching. At the time of Master ES and Master of the Playing Cards, for example, the lines employed were the same thickness along the shaft of the strokes reflecting the type of burin used to engrave the lines. With the invention of the échoppe (i.e. an etching needle with a oval-sectioned end) by Jacques Callot (c.1592–1635) the mechanical regularity of the early engravers’ lines used for shading gave way to etched lines of varying thickness that could be manipulated to swell when depicting dark areas of an image and become thin when depicting lit areas (see diagram and detail below of Callot’s The Nobleman with Fur coat).

|

(left) Callot’s swelling style of line

(right) Detail of Callot’s The Nobleman with Fur coat, 1624

|

Subtleties, such as Callot’s phrased swelling of line and Schongauer’s curved cross-hatching, became an important variable in Goltzius’ application of the dotted lozenge style. For instance, in Goltzius’ engraving, Marcurius (shown below), his phrasing and curving of the strokes articulate the surface contours of Mercury’s belly while Campagnola’s "dotted manner" renders the final stage of the tonal transition into light with a gentle merging of the inscribed marks with the white of the paper.

|

Detail of Goltzius’ Marcurius

|

|

Detail of Goltzius’ Marcurius

|

The flexibility of the dotted lozenge for showing the extremes of tone from the darkest shadows to brilliant light and its flexibility to express vitality by virtue of the swelling lines made the style popular with artists. This was especially true around the time of Goltzius as by 1585 there was strong interest in the expressive potential of theatrical exaggeration typifying the period style of Mannerism. For the Mannerists, such as Bartholomeus (Bartholomaeus) Spranger (1546–1611), whose paintings Goltzius translated into prints, the plasticity of modelling that the swelling line provided and the precision that the placement of the dots permitted lead to a new phrase in the art lexicon for describing the ultimate form of vitality: Sprangerism—a term exemplified by displays of voluminous muscles, contortion of the subject and bravura in laying closely aligned marks to render form.

Uploaded by the by ElicaTeam

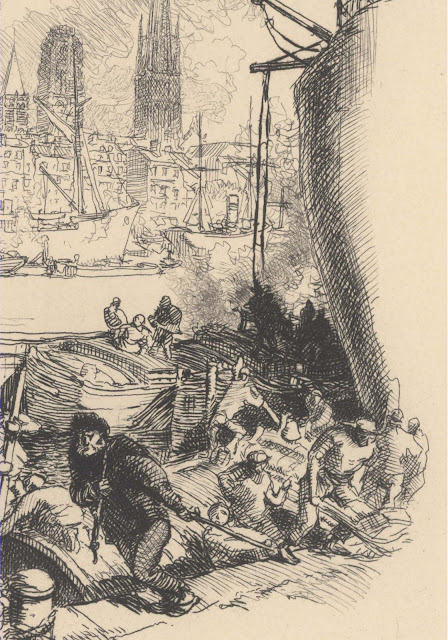

For instance, in Goltzius’ Vulcanus, compare the cross-hatched background beside Vulcan’s left leg (shown below) where no dot features in the matrix of lines with the dotted lozenge treatment of his leg (shown further below). From my observation, the background where there are no dots has moiré patterns, whereas Vulcan’s leg has no, or few, apparent patterns. Arguably, what is happening to the optical illusion is that the dot in the cross-hatched matrix disrupts the patterns from forming. But there is also an alternative explanation that has little to do with the dots causing interference: moiré patterns are minimised when the angle between the sets of parallel lines is close to either 45 or 90 degrees.

|

Detail of Goltzius’ Vulcanus showing moiré patterns in the cross-hatched background

|

There are many reasons for the abandonment of this versatile style towards the end of the nineteenth century: fresh ways of making images arose; the process of cross-hatching following by dotting is technically demanding and time consuming; and, the outcome can appear mechanical with resonance of a past era in printmaking. Like a lot of traditional styles, however, there will come a time for their revival when the time is “right.” A few decades ago the time was certainly not right but with the fresh ways of creating images now that the digital age has arrived, this may be the moment to reinvent the dotted lozenge.

In the digital experiments below, I have used some of the default filters in Photoshop to add new dimensions to the dotted lozenge in the hope that they may suggest ways to breathe life into this virtually forgotten style. The first pair of images explores the idea of reshaping the matrix of marks into a bas-relief. The second pair of images demonstrates the effectiveness of blur and lens flare filters to create tonal gradations that would not have been possible for the early printmakers. The final set of images explores alternative ways to change the dotted lozenge from negative (white) lines to positive (black) lines—a simple flick of a tool.

|

Dotted lozenge as bas-relief

|

|

Dotted lozenge with blur (upper image) and lens flare (lower image)

|

|

Dotted lozenge with transition from negative (white) lines to positive (black) lines

|