Bernard

Romain Julien (1802–1871)

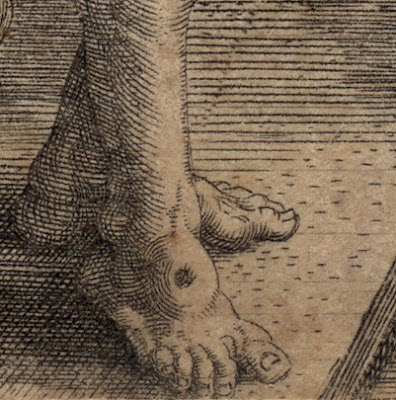

(left) “The Charging Chasseur” (aka “Officier de chasseur à cheval

de la garde impériale chargeant”, 1814–71

(right) “The Wounded Cuirassier” (aka “Le Cuirassier blessé

quittant le feu”), 1814–71

Both lithographs are after Théodore Géricault’s (1791–1824) paintings and were printed by

François Delarue (fl.1850s–1860s)

and published by Ernest Gambart (1814–1902)

in Paris.

Colour lithographs printed on heavy wove paper and lined with a

support sheet.

Size: (each sheet) 68 x 53 cm

Each lithograph is signed in the plate below the image by the

artist and inscribed: “Imp. Fois. Delarue,

Paris”

See a (brief) description of “Le Cuirassier” (“The Charging Chasseur”) at the Rijksmuseum: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.130348

Condition: both sheets have small tears (addressed with restorations to make them virtually invisible) and each sheet has been laid upon a heavy archival

support sheet.

I am selling this pair of huge and magnificently executed lithographs

by the famous master lithographer of the 19th century, Bernard

Romain Julien, for [deleted]. Postage for these prints is extra and

will be the actual/true cost.

If you are interested in purchasing these monumentally large prints,

please contact me (oz_jim@printsandprinciples.com) and I will send you a PayPal

invoice to make the payment easy.

These print have been sold

These images are so well known that they are almost icons of

nineteenth century art. What makes them special is certainly that they have the

capacity to grab attention and invite the imagination to take the viewer into

the portrayed reality of the scene. They are also milestones in art history marking the shift from cool objectivity, grand intentions and pictorial

cleanliness of Neo-Classical compositions to the dynamic diagonals, emotionally

charged marks and intimately personal visions of Romanticism.