What are some of the fundamental ways that viewer’s respond to imagery?

Although there are always issues complicating any simple answer to questions such as how an audience is likely to respond to artworks, at the heart of any discussion on this topic there are two fundamental ways. The first is a viewer’s automatic response to a portrayed subject. This is often described as “reflexive” (i.e. a response that is like an involuntary knee-jerk if one’s knee is tapped with a hammer). The second is a viewer’s conscious and mediated response that is often described as "reflective." This response involves the viewer in negotiating (i.e. “thinking about”) meanings based on associations, projections and interrogation of the visual information observed in the artwork.

Regarding a reflexive response, this is a natural reaction like the wish to wave away the fly engraved in Gerard de Lairesse’s (1640/41–1711) anatomical study, Table 52: Abdomen, Posterior Wall (shown below). Based on my own response, this fly and its proximity to the surgically evacuated abdomen cavity, along with its angled alignment towards the cavity and the fly's resting place on material bordering the cavity, gives me an involuntary shiver of unease. I instinctively want to brush it away so that the exposed diaphragm is uncontaminated by the fly’s presence.

|

Engraving by Abraham Blooteling (1640–1690) and Pieter Stevens van Gunst (1659–1724) after an illustration by Gerard de Lairesse (1640/41–1711) published in Govard Bidloo's (1649–1713) famous anatomical atlas, Anatomia humani corporis (

Table 52: Abdomen, Posterior Wall, 1690

copper engraving on cream laid paper with 2.5 cm chain-lines

(sheet) 50.4 x 34.6; (plate) 47.5 x 32.1 cm

Description of this print: “Large house fly shown on the specimen. Abdomen, posterior wall, in situ. Viscera removed to show diaphragm, crus of diaphragm around divided aorta and esophagus. Vertebrae and psoas muscle shown.

The splendid anatomical work of Bidloo is considered one of the most beautiful ones ever printed. It became famous because of the very elegant and elaborate engraved tables after drawings by Gerard de Lairesse, carried out by Abraham Blooteling and Pieter Stevens van Gunst.” (http://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/abdomen-posterior-wall-house-fly-417303811 [viewed 10 January 2014])

|

Vassar's Millionth Volume [Anatomia humani corporis by Govard Bidloo] (4.06 mins)

This reflexive response to the fly is also accompanied by an equally reflexive reaction of recoil at the grisly and uncommon subject portrayed—a dissected cadaver. Moreover, I have vacillating instinctive responses of revulsion and fascination with the contrast I see between the portrayed mechanical sheen of the dissection pins and the soft flesh that they hold in place (see details above).

The notion that my response vacillates between one moment of wanting to avert my eyes away from the portrayed scene and, at the next, with wanting to examine it in a searching way, is even more apparent when I look at another engraving from Bidloo’s anatomical atlas, Table 86: Dissected Foot (shown below). Here, the apparatus for displaying the dissected muscles and tendons is even more riveting to my eye in the sense that there is a note of theatricality in the way that the various body tissues are drawn apart by posts, pegs, callipers and pins. For me, I feel a twinge of pain, in terms of a gut reaction, when I see the muscles disassembled in this way.

There is another type of reflexive response that goes beyond gut-reaction and this is exemplified in Johannes Sadeler’s (1550–c1600) engraving, The Calling of Abraham (shown below). In this image, illustrating a scene from Genesis, the voice of God is portrayed by the Latin words: Egredere de terra tua (from the Genesis 12:1 verse: "dixit autem Dominus ad Abram egredere de terra tua et de cognatione tua et de domo patris tui in terram quam monstrabo tibi" [“the Lord said unto Abraham, get thee out of thy country and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house to the land that I will show you]). The written text is not the reflexive element in the image; rather it is the need for the audience to turn their heads upside down to read the inscription and in the act of doing this—perhaps blasphemously—to assume the position and role of God making the pronouncement from the heavens above. This device of inverting the text in the image is intentional. Sadeler wants the viewer to interact with the image in a physical way that causes the viewer to be God by an automatic unconscious response.

|

Johannes Sadeler (1550–c1600)

The Calling of Abraham, c1590

Engraving on fine laid paper with 2.8 cm chain-lines

(sheet) 22 x 26.7; (plate) 21.5 x 26.3 cm

Inscribed: (lower middle of the image) "Cu priuilegio / Sac. Cæs. M."; (lower margin) with two-line dedication to Augustinus de Justis: "IN GRATIAM PERILLVSTRIS COMITIS AVGVSTINI DE IVSTIS, PINXIT IACOBVS DE PONTO BASSAN, / VERONAE" and "Scalpsit autem Joann. Sadeler Belg."

Marvellous lifetime impression of the only state

Described by the

(http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3146681&partId=1&searchText=sadeler%2c+bassano&view=list&page=1 [viewed 12 January 2014])

Hollstein 53: Bartsch 7001.052

Isabelle de Ramaix offers the following information about this print: “The Jacopo Bassano painting which inspired this engraving is now lost, but at the end of the sixteenth century it was in the Giusti collection in

Condition: A superb lifetime impression that is neither bleached nor restored. The sheet is hinged with conservator’s tape but is not glued down onto a support sheet. The print shows signs of handling (bumped corners and a light fold mark across the centre but otherwise it is in good condition. I am selling this marvellous engraving for a total cost of $310 AUD including postage and handling to anywhere in the world. Please contact me using the email link at the top of the page if you have any queries or click the “Buy Now” button below.

|

To explain the difference between such reflexive responses and those that are reflective, I will return to my issue with flies.

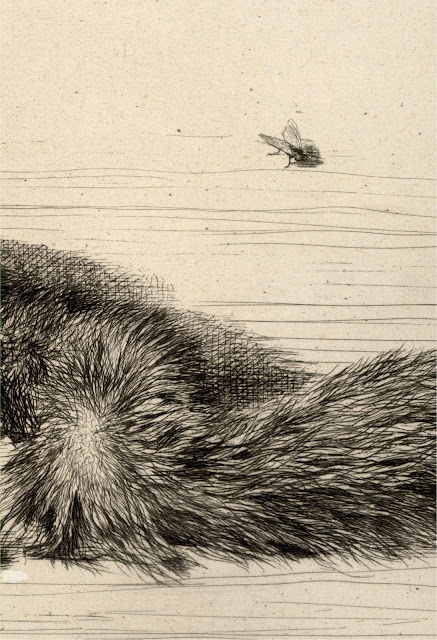

In Jules Jacquemart’s (1837–80), L’Écurueil et la Mouche? [The Squirrel and the Fly?] (shown below), the subject is again about death but when I look at the depicted fly, it does not arouse a reflexive response for me to brush it away. Instead, I ponder the fly’s relationship to the dead squirrel (i.e. I reflect upon the image) in terms of why Jacquemart choose to depict it. For instance, was Jacquemart simply illustrating a scene in a very objective way and the moment portrayed was when the fly landed on the ground beside the squirrel? Alternatively, did Jacquemart wish to allude to the history of vanitas and memento mori symbolism in art reminding us of the transience of life and that we too will die? Or from a more playful mindset, did Jacquemart have a wicked sense of humour in representing the fly as if it were a ball that the squirrel was toying with? In short, the fly does not trigger a reflective response but rather a reflective one in which my mind concocts reasons for what I observe in the print.

|

Jules Jacquemart (1837–80)

L’Écurueil et la Mouche? [The Squirrel and the Fly?], 1862

Etching on thick wove paper with wide margins

(sheet) 33 x 50.7 cm; (plate) 24.2 x 31.9 cm

Inscribed within the image (upper-right) “34” and in the margin (lower-left) “J. Jacquemart sculpt.”; (lower middle) L’ÉCURUEIL ET LA MOUCHE? / Paris Publié par A. CADART & CHEVALIER, Éditeurs, Rue Richelieu, 66.”; (lower-right) “Imp. Delâtre, St. Jacques, 303,

The print dealers, C & J Goodfriend, add to my questions about the significance of this subject with the proposals: “Or was he [Jacquemart] simply interested in delineating the textures and colors of the fur and a dead squirrel gave a far better opportunity than a live one? But then, why the fly? The ultimate question is: what is the significance of the question mark at the end of the title? Or is that a contribution of the typesetter – who didn’t know how to spell L’Écureuil? An interesting oddity and, as expected, supremely well etched.” (http://www.drawingsandprints.com/CurrentExhibition/detail.cfm?ExhibitionID=11&Exhibition=42 [viewed 13 January 2014])

Béraldi 330; Bailly-Herzberg (1863) 34; Gonse 330

Condition: Rich impression in very good condition but there is a light brown spot (more visible on verso) and a fleck/spot in the lower-left margin. I am selling this print for a total cost of $330 AUD including postage and handling to anywhere in the world. Please contact me using the email link at the top of the page if you have any queries or click the “Buy Now” button below.

|

To bring this discussion to a close, I have chosen to illustrate the many levels of reflective response that may be triggered with the example of William Hogarth’s (1697–1764), Time Smoking a Picture (shown below). Portrayed in this image is the worldly advice written in Greek on the upper edge of a framed painting: "Time is not a great artist but weakens all he touches.” To ignite a viewer’s reflective response in attempting to rationalise what this inscription could mean, Hogarth depicts the classical figure of Father Time seated on broken sculpture. For most viewers using their powers of reflective thinking, the placement of Father Time on the smashed sculpture suggests that art is destined to be ruined through misadventure over the passage of time. This reading of the impact of time on art is also sustained by Father Time’s scythe shown cutting into the framed painting. There is also the question that needs answering: why Father Time is blowing pipe smoke onto the painting? This may be harder to rationalise—unless a viewer understands that there was a leaning by collectors in the art market during Hogarth's era to value yellowed paintings (i.e. paintings that are antiques or where the varnish had the golden appearance of age). Hogarth symbolises the notion of time and the patina of grime that it can give artworks by showing Father Time literally darkening the framed painting inscribed with the curious text with smoke. In essence, Time Smoking a Picture is an allegorical warning to art collectors not to be duped into valuing artworks by the effects of time alone; a point that the Art Galley of NSW in its description of this print sums up succinctly: “time is not a beautifier but a destroyer.” (http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/8658/ [viewed 13 January 2013])

|

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Time Smoking a Picture, 1761

Etching and aquatint on wove paper with wide margins (as published)

Heath edition, 1822, published by Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. This edition was the last printing from the original plates (later editions are smaller in size and are either reproductions or the plate has been recut).

(sheet) 65.5 x 50.3; (plate) 23.6 x 18.5 cm

Description by the

See also the drawing for this print: http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/7624/ (viewed 13 January 2013)

Condition: Rich impression from the original plate. The wide margins are free of foxing but there is age-darkening to the edges of the sheet, light dustiness and soiling (mainly verso) and there are signs of handling in terms of bumped corners. I am selling this print for a total cost of $286 AUD including postage and handling to anywhere in the world. Please contact me using the email link at the top of the page if you have any queries or click the “Buy Now” button below.

|