Pieter

de Jode II (aka Pieter de Iode; Petrus iunior de Jode; Pieter de Jonge Jode)

(1606–70/74)

“Portrait of Jan Snellincx” or “Ioannes Snellincx”, 1630 (published

in 1645), after Anthony

van Dyck (1599–1641), from the series “Icones Principum Virorum.”

Etching and engraving (the BM advise that there are “traces

of oxidisation on the plate”) on laid paper.

Size: (sheet) 26.3 x 17.9 cm; (plate) 23.4 x 15.3 cm; (image

borderline) 20.9 x 14.9 cm

Lettered below the image borderline: (centre) "IOANNES

SNELLINCX / PICTOR HVMANARVM FIGVRANRVM ANTVERPIÆ. / IN AVLÆIS ET TAPETIBVS."

Inscribed below the image borderline: (left) "Ant. van Dyck

pinxit. / Pet. de Iode Sculp."; (right) "Cum priuilegio."

State vii (of vii with the initials of Gillis Hendricx

burnished)

Hollstein 157 (Jode); Mauquoy-Hendrickx 1991 37.VII; New Hollstein

(Dutch & Flemish) 9 (Van Dyck; copy); New Hollstein (Dutch & Flemish)

91.VII (Van Dyck)

The British Museum offers the following description of this print:

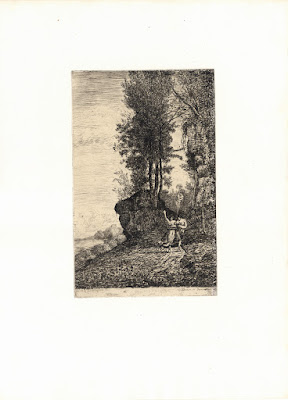

“Portrait of Jan Snellincx, half-length, turned slightly to the

right but facing the left; with moustache and goatee, wearing a scullcap, a

heavily draped doublet and a sash around his waist, his left hand resting on

his abdomen, clouds in the background; seventh state with the initials of

Gillis Hendricx burnished; after Anthony van Dyck Etching and engraving with

traces of oxidisation on the plate” (http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1427290&partId=1&searchText=R,1b.5.&page=1)

Condition: richly inked, crisp and beautifully printed impression

with good margins of approximately 1.5 cm in excellent condition for its age and

only a tiny closed tear at the upper-right corner. There are remnants of

mounting and previous collector’s notes verso.

I am selling this museum-quality print for the total cost of AU$206

(currently US$158.28/EUR138.62/GBP122.10 at the time of posting this listing)

including postage and handling to anywhere in the world.

If you are interested in purchasing this absolutely beautiful

etching (with engraving), please contact me (oz_jim@printsandprinciples.com)

and I will send you a PayPal invoice to make the payment easy.

This portrait of the Flemish painter, Jan Snellincx (1544–1638), is

arguably best remembered for his battle scenes and, as the Fritzwilliam Museum

points out, the “rising smoke in the background” of this portrait is perhaps an

allusion to such battle scenes (http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/vandyck/biographies/jansnellinck.1.html).

Although the print was inscribed by Pieter de Jode II, to my eyes the

original compositional arrangement crafted by Van Dyck—the preliminary drawing

for this print is now in the Duke of Devonshire’s collection at Chatsworth—is

what makes this print so engaging to contemplate. From my reading of the

composition, I see Snellincx responding jovially to someone, or some incident, lying

outside of the borderline of the image and I feel drawn into trying to

determine what he is thinking.

Beyond this marvellous portrait, Van Dyck had a much grander

vision. According to the curator of the British Museum, he envisaged creating:

“… a print publication containing portraits of the most prominent

men during his lifetime, divided into three categories: princes, politicians

and soldiers (16), statesmen and scholars (12), artists and art connoisseurs

(52). The initial idea could have been that Van Dyck would etch the faces (a

process possibly learnt from Vorsterman) while others would finish the plates in

engraving. Designs were needed for the plates and several drawings and oil

sketches (grisailles, sometimes in different versions) have survived. Van Dyck

only etched 17 plates himself, while he commissioned others to complete the

set, overseen by Lucas Vorsterman I (especially after Van Dyck settled in

England in the Spring of 1632). Although this project was started by Van Dyck

around 1630, he never saw it completed.” (http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1422752&partId=1&people=101862&peoA=101862-1-6&page=1)